Taken from, “GREAT MEN OF THE CHRISTIAN CHURCH”

Written by, Williston Walker

Edited and adapted for easier reading

To pass from the time of the Pauline epistles to the middle of the second century is to come into a very different world of thought.

The Old battle which Paul, the Apostle to the Gentiles, had bravely fought against the imposition of a legalistic Jewish yoke upon heathen converts, had become well-nigh forgotten ancient history.

The destruction of Jerusalem (A. D. 70) and the rapid growth of churches on Gentile soil had shifted the center of gravity of the Christian population, so that the vast majority of disciples were now of heathen antecedents. Of all parts of the Roman Empire, Asia Minor was that in which the church was now most strongly represented. Syria, northward of Palestine, Macedonia, and Greece were only in less degree its home. Probably it was already growing strong in Egypt. A close knit, extensive, influential, Greek-speaking congregation was to be found in Rome, and a group of small assemblies existed in the Rhone Valley of what is now France. Probably, but less certainly, the church was already well represented in the old Carthaginian region of Africa; but, in general, the Latin portion of the Empire was as yet little reached by the gospel.

Christians, though rapidly growing in numbers, were still chiefly from the lower classes of the population and of slight social influence. They were knit to one another by a common belief in God and Christ; a confidence in a divine revelation contained in the Old Testament and continued through men of the gospel age and subsequent times by the ever-working Spirit of God; a morality relatively high as compared with that of surrounding heathenism; and a confident hope that the present evil world was Speedily to pass away, and the Kingdom of God to be established in its stead. As sojourners separated from the world they owed each other aid, and developed a noble Christian benevolence.

Yet, though the Christianity of the middle of the second century had possessed itself fully of Paul’s freedom from Jewish ceremonialism, it was far from being Pauline. It did not consciously reject him; but it was unable to grasp his more spiritual conceptions of sin and grace and the significance of Christ’s death. Paul had been only one, if the greatest, of the missionaries by whom Christianity had been preached. To ordinary disciples of heathen antecedents, Christ seemed primarily the revealer of the one true God of whom heathenism had but dimly known, and was the proclaimer of a new and purer law of right living. God, through Christ, had revealed his nature and purposes, and had given new commandments which were to be fulfilled by chaste living and upright conduct. “Keep the commandments of the Lord, and thou shalt be well -pleasing to God, and shalt be enrolled among the number of them that keep his commandments,” said Hermas, writing at Rome between 130 and 140; and adding another utterly un-Pauline feeling of the possibility of works of supererogation: “but if thou do any good thing outside the commandment of God thou shalt win for thyself more exceeding glory. Fasting is better than prayer, but almsgiving than both,” said a preacher to his hearers a few years later, probably in Corinth or Rome.”

These changing conceptions of the Christian life were not the chief perils, however, which Christianity was encountering. It had come not into a world empty of thought. And, as we do now, that age attempted to interpret the gospel message in the light of its own science and its own conceptions. It had its own philosophies and its own religions with their secrets for those initiated into their mysteries. The result was a number of interpretations of Christianity, called in general Knowledge, (γνῶσις), the thought being that those who possessed this inner and deeper understanding knew the real essence of the gospel much better than the ordinary believer. Gnosticism had its beginnings before the later books of the New Testament were written. The Pastoral Epistles and the Johannine literature contain clear references to it (Examples would be; I Tim. I:4; 6:20; II Tim. 3:6-8; I John 4:2-3.). The Gnostics, however, as a full system of beliefs, did not however develop their power till the second quarter of the second century.

Gnosticism had many forms, but its essential feature was that it made the God of the Old Testament a relatively weak and imperfect being. It taught that the perfect and hitherto unknown God, far abler and better than the God of the Old Testament, sent Christ to reveal himself and to give men the knowledge by which they can be brought from the kingdom of evil to that of light. Since most Gnostics regarded this physical world as evil, any real incarnation was unthinkable, and Christ’s death can have been in appearance only. If his body was more than a ghostly deception, then Jesus was a man indwelt by the divine Christ only from his baptism to shortly before his expiring agony on the cross.

This thinking, though urged by men of great ability, denied the historic continuity of Christianity with the Old Testament revelation, it rejected a real incarnation, and it changed Christianity from a historic faith to a higher form of knowledge for the initiated, explanatory of the origin and nature of the universe. This Gnostic crisis was the most severe through which the church had yet passed; and its dangers were doubly increased when essentially Gnostic views of the Old Testament and of the inferior character of the God therein revealed, though by no means all the Gnostic positions, were advocated by a man of deep religious spirit, in some respects the first church reformer of history, Marcion.

Having come from Asia Minor to Rome about 140, Marcion broke with the Roman church in 144, charging it, –not wholly groundlessly, with having perverted Paul’s Gospel to a new Jewish legalism. To him Paul was the only genuine apostle; and he gathered a little collection of sacred writings, including ten of Paul’s epistles and the Gospel of Luke, but shorn of all passages intimating that the God of the Old Testament was identical with Him whom Christ revealed. All the rest of the apostles and of our New Testament writings he rejected. It was indeed true that the church of his day was very un-Pauline; but his Paulinism was of a type which Paul himself would have been the first to discredit.

To answer the Gnostics, the party within the church representing historic Christianity replied by gathering a collection of authoritative writings, the major part forms our New Testament; and presented their teachings by the preparation of creeds. The first Creed which was formed, is what we wrongly call the “Apostles Creed. The basis and authority of these creeds were established by appealing to the teaching handed down in the individual churches which were personally founded by the apostles, and whose authenticity was guaranteed by the continuity of those church’s officers. Out of this struggle, the rigid, doctrinally conservative, legalistic church of the third century —the Old Catholic church — came into being.

To these perils from within were added the dangers which sprang from popular hatred, due to heathen misunderstanding and jealousy, and to the occasional active hostility of the Roman government, which viewed the new religion as unpatriotic and stubborn because of the unwillingness of its adherents to conform to the worship prescribed by the state . Its feeling was much that which would animate many among us should any considerable party now refuse to honor the flag. To the unthinking, because they refused to join in the worship which the state required, the Christians seemed at once atheistic and unpatriotic. Popular superstition, because of their refusal to share in heathen festivals and their worship by themselves, –charged them with practices of revolting immorality. The Jews, also, though politically insignificant, were critical of Christianity; and, existing as they did in every large Roman community, their objections had to be met. These conditions determined Justin Martyr’s work. He would defend Christianity against its heathen Opponents, its Jewish critics, and its enemies within its own household. Hence the threefold battle which he fought.

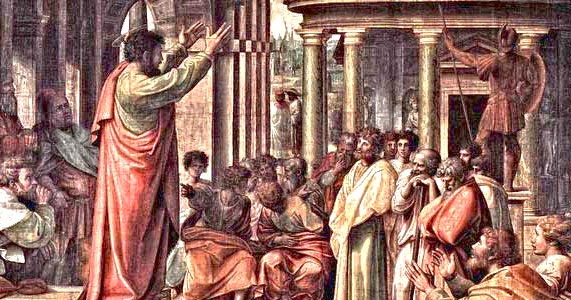

Justin Martyr, is one of the most characteristic Christian figures, and one of the most useful Christian writers, of the second century. He was a native of Flavia Neapolis, near the older Shechem, in ancient Samaria. Though thus born within the bounds of Palestine, and speaking of himself as a Samaritan, he was certainly uncircumcised and doubtless of heathen origin and training. It was not till after his conversion that he became familiar with the Old Testament.

Of the date of his birth nothing certain is known; but it must have been not far from the year 100. From early youth he was evidently studious, and he gives, in his Dialogue with Trypho, a picturesque account of his search for a satisfactory philosophy. His first initiation was through a Stoic, but when he sought knowledge of God this instructor told him it was needless. He then turned to the Aristotelians, but the promptness with which the teacher sought his fee made him doubt the genuineness of such interested claims. A Pythagorean next was sought, but this philosopher insisted on extensive preliminary acquaintance with music, astronomy, and geometry. Discouraged thus, Justin now turned with hope to a Platonist, and found real satisfaction in this most spiritual of ancient philosophies. He must have made no little progress in his new Studies, for he now adopted the philosopher’s cloak as his distinctive garb— a dress which he thenceforth always wore Yet, even while a Platonist, the constancy with which Christians met death impressed him, and led him to doubt the crimes with which they were popularly charged.

Nevertheless, it was through the gateway of his beloved philosophy that Justin was to be brought, however, into the Christian fold. As he tells the story, a chance meeting with an old man, as he walked by the sea, probably near Ephesus, resulted in a discussion in which his adviser turned his attention to the prophets as “men more ancient than all those who are esteemed philosophers, both righteous and beloved of God, who Spoke by the Divine Spirit, and foretold events which would take place, and which are now taking place Their writings are still extant.” The effect upon the inquirer was immediate and powerful. “Straightway,” he records, “a flame was kindled in my soul; and a love of the prophets, and of those men who are friends of Christ, possessed me; and I found this philosophy alone to be safe and profitable. Thus, and for this reason, I am a philosopher.

This conversion, whether the exact circumstances narrated are historic or are the product of Justin’s literary skill, actually did take place, and we may conjecture them occurring before A. D. I35, –and therefore before he had reached middle life. Further, this fundamental experience was in entire harmony with Justin’s previous philosophic training. Principally, because its central features were not, as with Paul, based upon a profound sense of sin, and of new life through union with Christ, but rather a conviction that God had spoken through the prophets and revealed His truth in Christ, –and in this message alone was to be found the true philosophy of conduct and life and the real explanation of the world here and hereafter .

To him the Old Testament was always the Book of books; but primarily because it foretold the Christ that was to come. For these truths he was willing to suffer; and to teach them became henceforth his employment. Just where he lived after this, and labored, it is in general impossible to say; but he was in Rome soon after the year 150, and it was there that he was later to meet his death. It was also at Rome, not improbably in 152 or 153, and certainly within the four or five years immediately subsequent to 150, that Justin wrote his noteworthy defense of Christianity against its heathen Opponents which placed him first among Christian apologists. This earnest appeal for justice— the ‘Apology’ is addressed to the emperor, Antoninus Pius (138-162) and his adopted sons, Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus.

In a direct and manly fashion, Justin calls upon these rulers to ascertain whether Christians are really guilty of the charges popularly laid against them and not to condemn them on the mere name. The Christians are accused of atheism, but they disown only the Old gods, whose existence Justin does not deny, but whom he regards as wicked demons. “We confess that we are atheists, so far as gods of this sort are concerned, but not with respect to the most true God, the Father of righteousness and temperance and the other virtues, who is free from all impurity.” “The Christians are charged with disloyalty to the Roman state,” Justin maintains, “but that is due to a misunderstanding of the nature of the kingdom that Christians seek. When you hear that we look for a kingdom you suppose, without making any inquiry, that we speak of a human kingdom; whereas we speak of that which is with God. Christians are not disloyal. On the contrary their principles make them the best of citizens. More than all other men we are your helpers and allies in promoting peace, seeing that we hold this view, that it is alike impossible for the wicked, the covetous, the conspirator, and for the virtuous, to escape the notice of God, and that each man goes to everlasting punishment or salvation according to the value of his actions. Christians worship God, Justin declares, rationally; not by destroying the good things he has given by useless sacrifices, but offering thanks by invocations and hymns for our creation, and for all the means of health, and for the various qualities of the different kinds of things, and for the changes of the seasons; and to present before Him petitions for our existing again in incorruption through faith in Him. Our teacher of these things is Jesus Christ, who also was born for this purpose, and was crucified under Pontius Pilate, procurator of Judea, in the times of Tiberius Caesar; and that we reasonably worship Him, having learned that He is the son of the true God Himself, and holding Him in the second place, and the prophetic Spirit in the third, we will prove.”

The last quotation shows that Justin’s view of Christ had not developed the form which we are accustomed to connecting with the doctrine of the Trinity, but judged by the standards of the fourth and fifth centuries. He does have a doctrine of the Trinity, but it is relatively unthought-out.

Yet his view of Christ is lofty indeed. It sees in him the divine activity always manifesting itself in the world, the constant outflowing of the wisdom of God, or we might say, the intelligence of God in action. Taking up the “Logos doctrine of the Stoic philosophers, so akin in many respects to that of the Fourth Gospel, and so easily combined with the conception of the divine “Wisdom,” set forth, for example in Proverbs. Justin taught that the divine intelligence had been always at work, not merely in creation and in the revelation of God to an Abraham or a Moses, but illuminating a Socrates or a Heraclitus, and the source of all good everywhere. In Jesus, this divine Wisdom was fully revealed. It, or to reflect Justin’s view we should say He, “took shape, and became man, and was called Jesus Christ.”

In speaking of Justin’s conversion, mention was made of the importance which he attached to the prophets and to the fulfilment of their utterances. They were men “through whom the prophetic Spirit published beforehand things that were to come to pass.” It was therefore natural that a large part of his Apology and of his Dialogue with Trypho was devoted to an exposition of such of their utterances as he believed bore on the life and significance of Christ; but he went much farther. Like Jewish writers before him, he looked upon the philosophers of Greece, especially his honored Plato, as having borrowed much from Moses. In Christianity was that true philosophy which all the philosophers, in so far as they have seen truth at all, have dimly perceived. The Jews, in his Opinion, had special ordinances, such as the Sabbath, circumcision, and abstinence from unclean meats, given them on account of the peculiar “hardness of their hearts;” but Christ has now established “another covenant and another law.” He has revealed God and God’s will to men; has overcome the demons who deceived men and delighted in their sins, whom Justin identifies with the old gods; and has appointed baptism as the rite effecting the remission of offenses. Christ’s work is, in Justin’s estimation, essentially that of a Revealer and Lawgiver, though he is not without some appreciation of the saving significance of his life and death and declares that “we trust in the blood of salvation.” This redeeming aspect of Christ’s work remains, however, relatively undeveloped in his thinking.

Thus, Justin defended Christianity against its heathen and its Jewish critics. He also replied to its foes of its own household, but his writings against Marcion are lost. His attitude may, however, be surmised from his declaration that the devils put forward Marcion of Pontus. The contest with Gnosticism was, indeed, strenuous; but charity toward those deemed “heretics” was never one of the virtues of the early church.

A most interesting glimpse is afforded in Justin’s Apology of the yet simple worship of the Roman church in the middle of the second century.

Admission to its membership was by faith, repentance, an upright life, and baptism, though in Justin’s view faith is primarily an acceptance of Christ’s teachings rather than as with Paul a new personal relationship. As many as are persuaded and believe that what we teach and say is true, and undertake to be able to live accordingly, are instructed to pray and to entreat God with fasting, for the remission of their sins that are past, we are praying and fasting with them. Then they are brought by us to where there is water, and are regenerated in the same manner in which we were ourselves regenerated. He who was baptized was counted fully of the church and shares in its worship. On Sunday the congregations gathered in city or country; the “memoirs of the apostles,” i. e., the gospels, or “the writings Of the prophets were read. Then the “president, for Justin avoids technical terms for church officers, verbally instructed, that is, preached a sermon. Next, all rose and prayed standing, the “president” doubtless leading, and the people responding “Amen.” Prayer ended, they saluted one another with a kiss. Bread and wine mingled with water were next brought to the “president,” probably by the deacons; and “after prayers and thanksgivings” offered by him, the Lord’s Supper was administered to those present, and the consecrated elements were taken by the deacons to the absent. The service closed with a collection, from which the necessities of widows, orphans, the ill, prisoners, and strangers were relieved; for the wealthy among us help the needy, and we always keep together.

A pleasing picture, surely, of the simple worship and mutual helpfulness of what it must be remembered were still close-knit little congregations, regarding themselves as separate from the world, and all too unjustly looked upon by it as misanthropic, unpatriotic, atheistic, and guilty of secret crimes. Justin himself was to receive the crown of martyrdom. After the composition of his Apology he left Rome, but of his journeys we know nothing, and he was back in the City where he was to die during the governorship of its prefect, Junius Rusticus, that is between 163 and 167, in the early part of the reign of Marcus Aurelius.

The account of his trial gives an interesting picture of the examination of a company of Christians at ‘the bar of Roman justice.’ In form, as in all ancient procedure, it was much like an examination in a modern police court, the judge questioning and sentencing the prisoners. Justin was brought before Rusticus, with six other Christians, one a woman, whom the judge evidently regarded as his disciples. Rusticus the prefect said to Justin, “Obey the gods at once, and submit to the Kings. Justin said, “To obey the commandments of our Savior, Jesus Christ, is worthy neither of blame nor of condemnation. Rusticus the prefect said, “What kind of doctrines do you profess?” Justin said, “I have endeavored to learn all doctrines; but I have acquiesced at last in the true doctrines, namely of the Christians, even though they do not please those who hold false opinions.” Rusticus the prefect said, “Are those the doctrines that please you, you utterly wretched man?” Justin said, “Yes, since I adhere to them with orthodoxy. Justin then tried to explain Christianity; but the judge soon cut him short. Rusticus the prefect said, “Tell me where you assemble, or into what place do you collect your followers?” Justin said, “I live above one Martinus, at the Timiotinian Bath; and during the whole time (and I am now living in Rome for the second time) I am unaware of any other meeting than his.” (Possibly Justin meant that his was the only school where Christianity was taught in Rome. See Harnack, Die Missiou and Ausbreitung des Christentums, p. 260.)

Whether this was literally so maybe doubted, but Justin does not seem to be unnaturally anxious to prevent persecution extending to his fellow-Christians. Rusticus said, “Are you not then a Christian?” Justin said, “Yes, I am a Christian.” Thus, satisfied of the guilt of the prisoner, the judge turned to his six fellow-accused, and tried to make several of them acknowledge themselves Justin’s disciples. They all promptly owned themselves Christians, but gave evasive answers as to Justin’s share in their conversion, doubtless wishing to shield him. But the judge was disposed to overlook the past provided the prisoners would now yield full obedience.

Here came, as in most early Christian trials, the real test of steadfastness; and a terrible test it was. A pinch of incense cast on the fire burning on the altar before the bench would have freed them; but it would, in the opinion of the time, have been a total denial of Christ. The prefect says to Justin, “Hearken, you who are called learned, and think that you know true doctrines; if you are scourged and beheaded, do you believe you will ascend into heaven?” Justin said, “I hope that, if I endure these things, I shall have His gifts. For I know that, to all who have thus lived, there abides the divine favor until the completion of the whole world.” Rusticus the prefect said, “Do you suppose, then, that you will ascend into heaven to receive some recompense? Justin said, I do not suppose it, but I know and am fully persuaded of it.” Rusticus the prefect said, “Let us, then, now come to the matter in hand, and which presses. Having come together, offer sacrifice with one accord to the gods. Justin said, “No right-thinking person falls away from piety to impiety. Rusticus the prefect said, “Unless ye obey, ye shall be mercilessly punished. Justin said, “Through prayer we can be saved on account of our Lord Jesus Christ, even when we have been punished, because this shall become to us salvation and confidence at the more fearful and universal judgment-seat of our Lord and Savior. Thus, also said the other martyrs: “Do what you will, for we are Christians, and do not sacrifice to idols. Rusticus the prefect pronounced sentence, saying, “Let those who have refused to sacrifice to the gods and to yield to the command of the emperor be scourged, and led away to suffer the punishment of decapitation, according to the laws.

So died a martyr for his faith, and one of the most deserving of the Christian leaders of the second century.