Written 3/21/2011, by FREDERICK SCHMIDT

Sourced from: Patheos

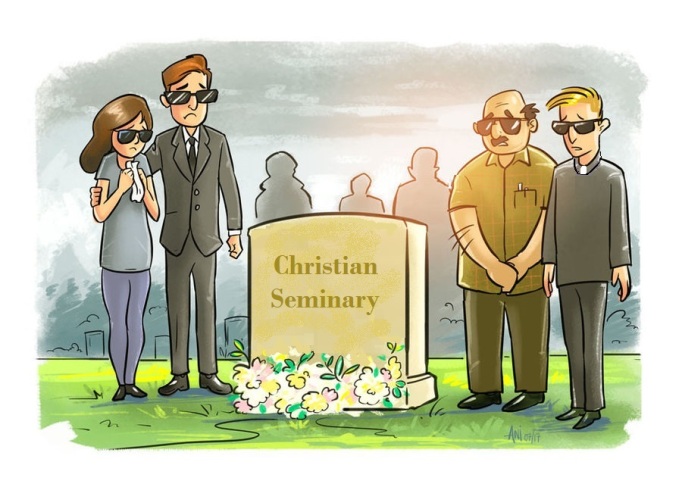

Our seminaries are dying and the Master of Divinity degree has been discredited.

Bishops and other church leaders once believed both were essential to effective ministry, but today they are considered one of several routes to ordination and an increasing number of church leaders are arguing that attending seminary may actually be detrimental to the process they once considered the gold standard.

A large number of the mainline seminaries are selling their buildings and property, cutting faculty, and eliminating degree programs. Those that are not, are competing for a shrinking pool of prospective students and rely on scholarships and lower academic standards to attract the students that they do have.

There are countless reasons for the crisis, some of them as old as the professional preparation of clergy itself.

In the quest for academic respectability, seminaries have not always remembered that preparing clergy was the mission and lifeblood of their institutional life. Some have focused on preparing scholars, which though essential, is secondary to its primary ministry of preparing new generations of spiritual leaders.

Some have prepared students who lacked the practical skills to effectively lead a congregation. Others have produced students who were so poorly grounded in the Christian faith that they lacked the necessary spiritual formation to be effective.

Changing trends in theological education often truncated and colored the theological education that many received. In the ’60s, seminaries prepared a generation of seminarians that rightly attended to issues of social justice. That was fair enough—sin has its corporate dimensions.

But some professors argued there was really little else to the Gospel and soon the church’s teaching on justice became little more than a brand of political discourse. In the ’70s and ’80s, this trend gave way to the importance of pastoral counseling. Here, too, there were important lessons to learn, including the realization that many people are defeated spiritually by psychological and familial systems that, narrowly speaking, cannot be easily traced to any classical definition of sin.

But, as with other excesses spawned by trends in theological education, the net result was a generation of clergy who practiced unlicensed therapy.

Now the trend is leadership and there can be little doubt that among the next generation of graduates will be the aspiring CEOs. There has never been any doubt that the church needs to be better led, but one has to wonder how much spiritual guidance there is to be had at the hands of clergy who think of themselves as ecclesiastical managers.

Seminary faculty often lack any real affinity for the church and, that too, has colored the kind of graduate that seminaries have produced. In part this state of affairs can be traced to the seminaries themselves, which hired faculty from a wide array of institutions, including many that were shaped not so much by theological categories as they were the assumptions of religious studies programs. But churches also made it difficult, if not impossible, to be ordained and, at the same time, prepare for an academic career. The complaint that anyone with a Ph.D. isn’t really interested in the church or is looking for advanced placement is a common refrain sung by bishops, boards, and commissions charged with overseeing the ordination process; and it thins the ranks of those committed to serving the church in her seminaries.

Faculty have also indulged their academic interests, creating both classes and curricula that correspond with their research issues and academic agenda but don’t necessarily speak to the basic and perennial needs of the church’s ordained ministry. The net result is a Master’s degree that is often skewed to allow as many electives as possible and catalogues filled with boutique courses that have little application to pastoral ministry. Likewise, seminaries have trimmed academic requirements in some essential fields to the point that graduates often have little more exposure to the Old and New Testaments than a general introduction to each and one elective. In most cases a biblical language requirement is completely missing, and the elective could be as arcane as a class on “Bach and Romans.”

In spite of the fact that there is room for so many extras, the degree itself is bloated and expensive. The Association of Theological Schools require at least 72 hours of course work, but some seminaries require as much as 106 hours; and the inside joke among most seminarians is that they will be fortunate to crowd three years into four . . . or five.

Meanwhile, whatever the canon law or discipline of mainline denominations may appear to suggest, the church has failed to articulate what it wants from its seminaries and its graduates.

The church uses seminarians to fill the chinks in its clerical armor, appointing them to serve in churches long before they have completed the education that is needed to do their work safely and with integrity.

Denominations have left seminarians to pay for their educations, saddling them with debt that they cannot comfortably repay because beginning salaries for clergy are often below the poverty level. And, at the same time, they have offered alternative routes to ordination bypassing seminary entirely, leaving those who do go to wonder why they worked so hard to accomplish the same goal. What we will never know is how many prospective clergy are lost because they conclude that if the ministry is something you can do without preparation it isn’t really worthy of their attention.

To make matters worse, most mainline churches give little more than fitful attention to the formation and support of clergy. Relying on the occasional workshop and briefing from denominational lawyers, churches are effective at insulating themselves from liability for clergy misconduct, but there is often little more attention given; and in the earliest stages responsibility for the effective preparation of ordinands is being tossed back and forth between the church and the seminary, leaving the ordinands themselves to pick their way through a conflicting minefield of expectations.

Seminarians often head off to school, uproot their families, and begin paying tuition bills with little clear indication from their churches that their denominations share their enthusiasm for their vocation; and there is little honest information about the shape of the opportunities that lie ahead. In some cases a seminarian can wait five to seven years before learning if she will be ordained, and in the meantime he is forced to run a gauntlet of committees and requirements that is more akin to hazing for membership in a fraternity, than it is serious preparation for ministry.

So, should we throw the system out, disband our seminaries, and launch even more deeply into the brave new world of clergy preparation? Should we throw the task back on the churches, requiring each one to grow its own clergy? Or should we rely on regional choices and an array of on-line approaches? All of those options are currently in play.

Realistically speaking, I am afraid that we will limp along with a struggling seminary system and a church that never quite clarifies what it wants from its clergy. As one bishop told me, “We (bishops) don’t have strategic conversations about this or anything.” Although he spoke for his own denomination, I have no doubt he could have spoken for many others. In the absence of bold, creative leadership there is little chance that things will change. Only time and Darwinian forces may resolve the dilemma. But I am equally certain that the survival of the fittest will not provide the church with the faithful, sophisticated leadership that it needs and deserves.

If the world of theological education were mine to remake—and it is not—I would be guided by the following convictions:

One, rigorous academic preparation is absolutely essential to creative, competent, servants of Christ who are deeply formed and capable of forming others.

Two, that kind of preparation is more important than ever before. We live in a complex and fast-changing world that will require a generation of leaders who are as well trained and educated as are the people in any other profession. It is a crime and miscarriage to require anything less.

I often tell my students, “If you were laying in the operating room and some one bounded in and declared, ‘Hi, I’m Fred, and I don’t know a thing about anatomy or the practice of medicine, but I just love the idea of serving God through surgery,’ you would use your remaining moments of consciousness to roll off the gurney and claw your way down the hall. And yet it was Jesus who said, ‘Fear not those who can kill the body, but those who kill the soul.'” Churches that fearfully cast around for quick fixes to the training of clergy, give it scant attention, and then abandon their priests and pastors to the vagaries of forming themselves cannot expect to be a spiritual force in the world. Nor can they expect their clergy to be positive spiritual forces in the lives of others.

Three, I am also convinced that as many new creative approaches to education as there might be, a residential model of focused, face-to-face education and formation in the faith is the best means of preparing a generation of thoughtful, faithful servants of the Gospel. This is not to denigrate those who have been encouraged by the church to pursue alternative means of completing the requirements for ordination. It is to say that the church should instead make resources available for all those who do pursue the church’s ministry to avail themselves of that face-to-face formation.

So, many will argue that what I have outlined below is impractical, but this is what I would do:

Candidates for ordination would be required to:

1. Attend seminary and complete a Master of Divinity.

2. Prepare in a residential setting.

3. Select their schools from a well-honed list of seminaries.

4. And perform at the top of their ability.

In exchange, the church would:

1. Help to pay for a significant amount of their education.

2. Provide close, caring, thoughtful, formative companionship along the way.

3. Support a handful of seminaries financially in their effort to prepare their ordinands.

4. Provide their candidates with an early, honest, responsible evaluation of their candidacy. (The ordination process should not take more years than the forming of doctors and lawyers.)

5. Abandon alternative approaches to ordination, confining its attention to preparing properly everyone it does ordain.

6. Do what it takes to see that new clergy receive a living wage.

7. Support the best and the brightest of their clergy in academic formation and pursuits, seeing them as an extension of the church’s teaching ministry.

In return the seminaries would promise to:

-

Create a Master of Divinity that is lean and designed to do what it should do, covering a set of definable core competencies that were offered and taught—no more, no less. (The M.Div. is not a research degree; it is a professional degree analogous to the Juris Doctorate required of lawyers and it should be treated as such.)

-

Educate and spiritually form the students sent to them.

-

Enlist a faculty that is both willing and able to teach an essential body of knowledge and skills, as well as teach the faith.

-

Communicate effectively and often with the church about the preparation of its candidates.

The result would be fewer ordinands and students then there already are.

But if churches and seminaries focus on the rigorous formation of clergy we could produce a generation of leaders who, God willing, might change the world and save mainline Christianity.

The alternative is to limp and wander into the future, trusting Darwin with the lives of our clergy, seminaries, and churches. If we do, others will preach the Gospel, but God will not compensate us for faithless, feckless, unimaginative neglect.