Concealing his anger, and especially his dark design…

…the archbishop sent a message to Patrick, to the effect that he much wished to receive a visit from him at St. Andrews, in order to hold a conference on such points in the administration of the church as might seem to require reformation. The invitation reached the young reformer only a few days after his marriage. Hamilton perfectly understood its meaning, and the issue to which it was intended to lead. Indeed, he said to his friends that in a short time he would have to lay down his life.

His mother, his young wife, and the rest of his friends, gathering round him, besought him with tears not to go to St. Andrews. But be was steadfastly minded this time hot to flee. Who could tell whether the hour had not come when a great sacrifice would effect the liberation of his country. He set out for what Howie calls ” the metropolis of the kingdom of darkness.”

On arriving at St. Andrews he found the archbishop all smiles; in fact, he met a most gracious reception from the man who had inwardly resolved that he should never go hence. Lodgings were provided for him in the city. He was permitted to move freely about, to converse without restraint with all classes, and to avow his opinions without the least concealment: even the halls of the university he was permitted to enter, and discuss with doctors and students touching the rites, the sacraments, the dogmas, and the administration of the church. Thrown off his guard, the young evangelist made ample use of the freedom accorded him, and when he heard the echoes of his own sentiments coming back to him amid the halls and chairs of that proud seat of the Papacy, the ” Scottish Vatican,” he began to persuade himself that the day of his country’s deliverance was nearer than be had believed: he thought he could see rifts in the black canopy over the land. And in truth these labors were not in vain; for if they helped to conduct the reformer to a scaffold, they helped powerfully in their issue to conduct Scotland to the light of the gospel.

Among the canons of St. Andrews at that time was a young man of rare parts, already distinguished as a scholar, especially in scholastic learning; but be was all on the side of Rome. In fact,he had done battle with great applause against Lutheranism. On this young canon the priests built the greatest hopes; his name was Alane, or Alesius, a native of Edinburgh. The young canon, full of zeal for ” holy church,” and on fire to break a lance with the “heretic,” waited on Hamilton in the hope of confuting him. He returned converted: the sword of the Spirit had pierced, at almost the first stroke, through all the scholastic armour in which Alesius had encased himself, and he dropped his weapon to the man be had been so confident of vanquishing. The young convert afterwards became eminent as a reformer.

After Alesius there came another combatant to Hamilton, as eager to do battle for the old faith, and as confident of victory as the former. This new disputant was Alexander Campbell, prior of the Dominicans. He too was a person of parts, accomplished in the learning of those days, and kind and candid in disposition. He visited Patrick at the request of the archbishop, who, feeling strongly the hazards of bringing such a man as Hamilton to the stake, was not unwilling to avoid the hard necessity by bringing him back to the doctrine of Rome.

He ordered Prior Campbell to spare no effort to recover the young and noble heretic. Campbell had an interview with Hamilton, but soon found himself unable to sustain the argument on the side of Popery, and acknowledged the corruptions of the church and the need of reform. The conversion of Alesius seemed to have repeated itself in that of Campbell, and the two men, Hamilton and the prior, freely unbosomed their sentiments to one another.

After a few days the archbishop, scenting, it would seem, the leanings of Campbell, summoned the prior to report what progress he had made with Patrick. In the presence of the archbishop and his councilors the prior lost his courage. He revealed all that Hamilton had communicated to him: he acted in the archiepiscopal palace a different part from that which he had sustained in the chamber of the reformer. He was no longer the disciple, but the accuser. He consented to become one of Hamilton’s judges. He knew the truth, but when he came to make his choice between the favor of the hierarchy and the gospel, he was unwilling to surfer the loss of all things that he might win Christ.

Hamilton had now been a month at St. Andrews. He had all that time been busily employed discussing and arguing with doctors, priests, students, and townspeople; and not in vain. That this should be done at the very seat of the primate shows one of two things; that the hierarchy believed its power so firmly rooted in this city that nothing could shake it, or, and this is the more probable, that the priests hesitated to strike when the intended victim was so nearly related to the king. But the delay, if it furnished Hamilton’s enemies with the proof they sought against him, contributed much to the early triumph of the Reformation in Scotland.

In that little month there was scattered on this most important field a great amount of that incorruptible seed that liveth and abides for ever; and which watered, as it soon thereafter was, with the blood of him who sowed it, sprang up and brought forth much and good fruit.

But the matter would admit of no longer delay. Hamilton was summoned to the archiepiscopal palace to answer to a charge of heresy. This brought the matter to a bearing on both sides. That the charge would be proven there could not be a doubt; and the convicted heretic could in those days have no other doom than the stake. To all this length, then, had the archbishop resolved to go; and so too had the reformer; his friends, seeing death in the summons, exhorted him to flee. He was deaf to all their entreaties; he had returned from Germany steadfastly minded, if need were, to glorify God by his death. He obeyed the summons of the arch bishop,well knowing what would come after.

Before accompanying the young evangelist to the tribunal which were behold assembling in the archiepiscopal palace, let us glance at the precautions his persecutors have taken to enable them to proceed in their work without interruption. The side on which it behoved them first of all to guard themselves was the king. The frivolous James V. took a real interest in his relative,the young evangelist. The luster of his genius and the grace of his manners, in fact everything about him but his heresy, had attractions for the monarch; and knowing, most probably,how the priests meant to handle him, he counseled him to reconcile himself with the bishops. Priest-ridden though the king was, it was not safe for the bishops to conclude that he would stand by like an utter coward and see them burn the young Hamilton.

Means were found to send the young monarch, who was then only seventeen, out of the way. There was a famous shrine in Ross-shire, St. Duthac, to which James IV had often gone in pilgrimage. The king was told that his soul’s health required that he should, after his father’s example, do penance at that shrine. It was the depth of winter; but if the roads were rough and, it might lie, filled in some places with snow, the merit of the journey would be all the greater, and so too would the time spent upon it, and this last was of prime consideration to the Bishops. Obedient to this ghostly counsel the king started off on his distant pilgrimage. Another danger threatened in a quarter not so much at the command of the priests.

Tidings readied the manor-house of Kincavel of the perils which were closing round Patrick. The alarm and anxiety these tidings caused to his family may well be imagined. There was but one part which it became his brother, Sir James Hamilton, to act in the crisis, and he immediately set about it. He was sheriff of the county and governor of one of the king’s castles; and so, assembling without loss of time a body of men at-arms, he put himself at their head and set out for St. Andrews. Marching along the shores of the Forth the troops arrived at Queensferry, where they intended crossing the firth. But alas, it looked as if the elements were fighting on the side of the archbishop. A strong gale was blowing from the west, and the tumult of the waves in the narrow strait was so great that passage was impossible. Sir James, while the hours were gliding away, could only stand and gaze in despair on the tempest that continued to rage without sign of abating.

Meanwhile this assemblage of armed men on the southern shore of the firth was caught sight of by the friends of Beatoun in Fife, and their purpose guessed. This being told the archbishop,he gave orders that a troop of horse should be dispatched to meet them.

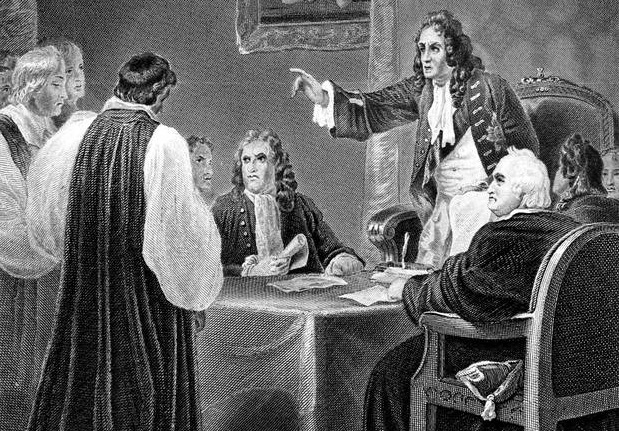

We return to St. Andrews. Patrick Hamilton rose early on the morning of that day on which he was to appear before the tribunal of the archbishop, –The first rays of the sun had just lighted up the waters of the bay and kindled the hills of Angus beyond, when the reformer was already seen traversing the streets on his way to the palace of the archbishop. It was between seven and eight o’clock when Beatoun was told that Patrick Hamilton was waiting admission. His thought was to see and converse with the archbishop before the council had met; the members of the council were already met, and’ consulting together how best to confute the reasonings of the man they had summoned to answer at their bar.

Beatoun immediately constituted the court; Hamilton was introduced, and the accusation was read. “You are charged,” said the commissioner, “with teaching false doctrines: First, that the corruption of sin remains in the child after baptism; second, that no man is able by mere force of free will to do any good thing; Third, that none continues without sins so long as he is in this life; fourth, that every true Christian must know that he is in a state of grace; Fifth, that a man is not justified by works, but by faith alone; sixth,that good works do not make a good man, but that a good man makes good works ; seventh, that faith, hope,and charity are so closely united, that he who hath one of these virtues hath also the others; eighth, that it may be held that God is the cause of sin in this sense, that when he withholds his grace from a man, the latter can not but sin; ninth, that it is a devilish doctrine to teach that remission of sin can be obtained by means of certain penances; tenth, that auricular confession is not necessary to salvation; eleventh, that there is no purgatory; twelfth,that the holy patriarchs were in heaven before the passion of Jesus Christ; and thirteenth, that the pope is antichrist, and that a priest has just as much power as a pope.”

Having heard this list of charges the reformer made answer thus: “–I declare that I look on the first seven articles as certainly true, and I am ready to attest them with a solemn oath. As for the other points,they are matter for discussion; but I cannot pronounce them false until strong reasons are given me for rejecting them than any I have yet heard.” There followed a conference between Hamilton and the members of council on each article.

Finally, the whole were referred to a committee selected by the archbishop, who were to give their judgment upon them in a few days. Pending their decision Hamilton was allowed to see his friends, to engage in discussion, in short, to enjoy in all respects his liberty. It was evidently the design of his enemies to veil what was coming till it was so near that no one should be able to prevent it.

—————————————-

Taken from, The Scots Worthies, Their Lives

Written by, J.A. Wylie

Spottiswood, History of the Church of Scotland

Calderwood, History of the Kirk of Scotland,vol. 1.